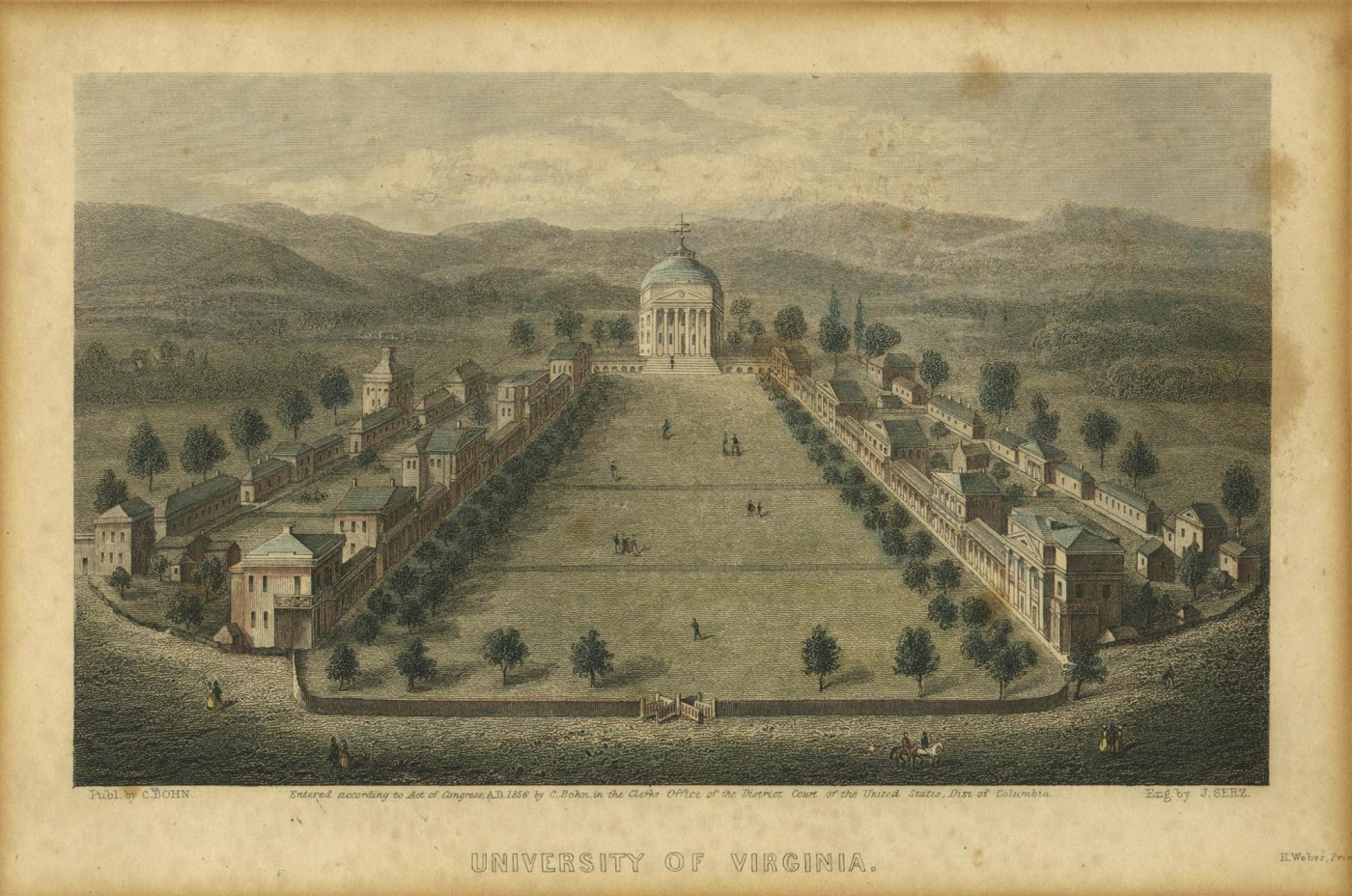

A landscape architect for president. How about it? In the first part of this feuilleton this idea turned out to be not as far-fetched as it sounds…. All first American presidents were gardeners/farmers, using their own garden to experiment with and express their ideas on what the future America should be, with Thomas Jefferson as their champion. In part III we will see how Thomas Jefferson’s close-knitted relationship between gardening, garden design, landscape architecture and politics becomes manifest when he translated the experiments with his own garden Monticello to the University of Virginia, materialising his democratic ideals.

Jefferson had been involved in every detail of the university, from its foundation to the design of the buildings and gardens. He envisioned a new kind of university, where students and faculty could interact, live and learn all together, and dedicated to educating in practical affairs and public service rather than in more academic professions. It was the first non-sectarian university in the United States, revolutionary for its time in terms of its curriculum, educational methodology and physical form. Both programmatically – the combination of classrooms and living quarters – and spatially – the spreading of the academic buildings into the landscape as a unified, harmonious interrelation – the composition of the university displayed a new way of thinking.

The university, which opened in 1825, is designed around a lawn, terraced down in order to deal with the hilly topography of Charlottesville and flanked on each side by a formal alley of trees, with at the end the library – inspired by the Pantheon in Rome – as the majestic centre-point. The lawn’s edges are defined by a series of educational pavilions with student housing between them, connected by a continuous colonnade. The lawn is the formal garden and main public space of the campus, in opposition to the more private rear gardens of the pavilions.

Its precedents can be found in the quadrangles of the English university towns Oxford and Cambridge. However, unlike the air of exclusiveness of its European predecessors, the American lawn, opening up to the unbounded landscape, reflected both domesticity and community, in an amalgam of an ideal of romantic pastoralism and democratic communalism. It promoted a community ideal, and the critical conception that a place can create community.

For further reading: Therese O’Malley, “The Lawn in Early American Landscape and Garden Design,” in The American Lawn, ed. George Teyssot (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).